Longform - New Orleans - Fertel

THE DEAD MUSEUM

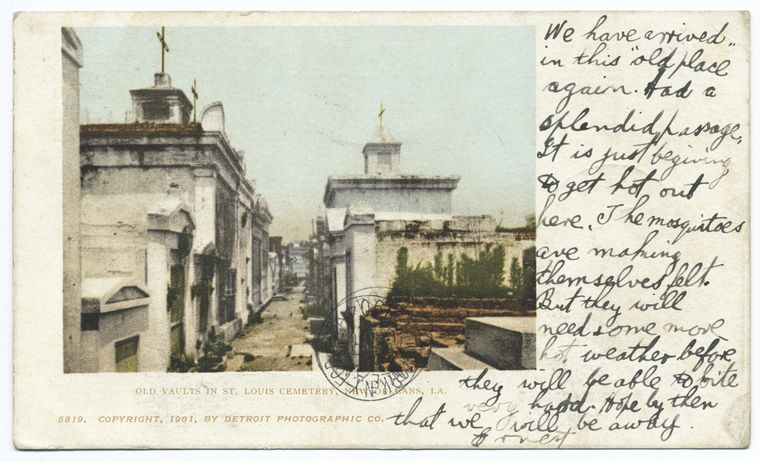

Life and death in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1

BY RIEN FERTEL

In New Orleans, there is often more life in death than life in the living. T-shirts feature the lives of the recently deceased, while the newspapers’ obituary pages rank second only to Sports in popularity. Funeral homes charge extra to construct dramatic, lifelike funeral poses: standing on two feet, for example, or seated in a garden with a cigarette and glass of champagne in hand. Neighborhood streets often fill with jazz funerals that dance the departed souls into the afterlife. Weather, termites, poverty, even plain old indifference all cause our houses and hospitals and schools and levees to succumb to a state of atrophy that some find frustrating, but most often describe as picturesque and charming. Famously, the city is gradually sinking, an inch annually in some neighborhoods, while the coastline gets nearer by the day. It might be said that we’re slouching towards Hades.

The author William S. Burroughs understood the city's obsession with the departed. "New Orleans," he writes in Naked Lunch, "is a dead museum."

But nowhere do the dead remain more present than in the city’s cemeteries. “A New Orleans cemetery,” the distinguished local writer Walker Percy wrote, “is a city in miniature” that can often seem “at once livelier and more exotic” than the city’s other architectural achievements: its renowned sidewalk corners, verdant gardens, and music clubs, which all jive and hum and bounce to their own life-affirming rhythms.

During its normal hours of operation, through frequent rainstorms and unremitting humidity, New Orleans’s most notable city of the dead, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, overflows with life. Visitors arrive by horse-drawn carriage, taxi, and rockstar-sized tour bus at the cemetery’s front gates, where vendors hawk bottles of water and lemonade alongside guides offering unlicensed, not to mention dubious, historical expertise. Zombie-like clusters of thirsty tourists lurch along the cemeteries’ main avenues and side paths to photograph and pose alongside the aboveground vaults, most of which are tall and boxy, constructed of brick and plaster, and adorned with a simple, marble plaque.

Towards the cemetery’s center, women covertly lavish lipstick kisses on the future final resting place of Nicholas Cage — yes, that Nicholas Cage — who several years ago built a nine-foot tall, gleaming white pyramid amid a clump of crumbling, weathered crypts. In New Orleans, even the dead are not safe from gentrification.

Though New Orleanians have a deep and rich history of visiting cemeteries in order to feel more alive, the vaults at St. Louis No. 1 — some of which date to the cemetery’s 1789 founding — tend toward rot and decay. Families move away, die off, or, most typically, lose interest in visiting distantly-related, long-dead ancestors. The local Catholic Archdiocese refuses to pay for upkeep, unless a perpetual care plan has been purchased. Until recently, the cemetery operated in a sort of no-man’s land, sandwiched between the French Quarter’s seedy backside, the long-underutilized Armstrong Park, and the now former Iberville Housing Projects. A trip to the cemetery could quite literally result in death.

Rewatch the famous scene from Easy Rider, when Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda take their French Quarter escorts on a post-Mardi Gras acid trip. Between the psychedelic freak-outs and nude bodies, the camera’s eye pans up, over, and around a cemetery’s tombs. Some are perfectly plastered, brightly whitewashed. But most suffer from various states of disrepair: sprouting with weeds and shrubs, brittle and broken, collapsing into themselves. This is St. Louis No. 1. And it looks very much the same now as it did in the late 1960s.

It is estimated that seventy-five percent of the tombs in St. Louis No. 1 are orphaned. Without caretakers, the vaults are easy prey to midnight marauders, tomb raiders of marble and trinkets and bone, disturbers of the afterlife. Perhaps even more detrimental to a vault’s durability is the chimerical notion, regularly perpetrated by some tour guides, that scratching a series of three Xs into a tomb’s soft, mortar exterior will result in a wish made real.

The city’s most famous tomb, as well as the likely ground zero of the triple-X scratchitti myth, belongs to Marie Laveau. Recently an unknown vandal painted the famous voodoo priestess’s crypt a vibrant shade of pink. Whether practical joke or feminist art project, whimsy turned to angst when a local expert revealed that the latex-based paint would trap moisture inside, not allowing the vault’s contents to “breath,” thus confirming that fresh air is not just for the living.

* * *

Once a month, about three dozen locals and visitors volunteer to spend their early Saturday hours tidying up the homes of the dead with Save Our Cemeteries, a nonprofit that has, since 1974, striven to preserve thirteen of the city’s neglected historic cemeteries through fundraising and expert-guided walking tours. The organization’s home cemetery is St. Louis No. 1, where they can be most visible, do the most good, and push back against a ceaseless tide of blight.

One breezy and blue April morning, I was tasked, together with two other volunteers, with scrubbing the exterior of a particularly ramshackle vault with a gallon-sized spray bottle of mild soapy water and a soft-bristled brush, so as not to mar the fragile plaster walls.

But the tomb needed more than a good washing. It needed a full facelift. The vault’s foundation and face were cracked with scars. Plaster peeling, its bricks exposed and turning to dust, the tomb colors that of desiccated flesh. Grass grew from its top and sides. What plaster did remain was decorated with so many XXXs that it resembled a cross-stitched quilt. Its marble plaque, designating who was buried within, had long been pried off and carted away — the resultant opening was crudely bricked over. Sad and shabby, this tomb was much more than an orphan. It was nameless, its anonymous owners lost to time.

I began to carefully scrub away.

Though it felt entirely uplifting to volunteer a Saturday morning away, cleaning this rather unremarkable crypt selfishly clicked with the little niche I had begun to carve out for myself. In school classrooms and scholarly work, I teach and write about the chronicles of my city’s past.

This volunteer opportunity was also a celebration of sorts, a chance to get outside, away from my writing desk, and just breath. One month earlier I had successfully defended my doctoral dissertation in American History. My research focused on a now obscure literary circle from New Orleans, a close-knit community of nineteenth-century poets, playwrights, and pianists; novelists and journalists; historians and opera composers who promoted the idea that their city’s past was exceptional, that their shared history made them different. They did not consider themselves French, though they principally spoke and wrote in that tongue. They were not impelled to call themselves Americans, yet they claimed United States citizenship and all the freedoms and failures this democracy entailed. Their tropical climate aligned more with the Caribbean than along the lines of their Confederate neighbors, while their nascent culinary and musical cultures were rooted in Africa.

They inhabited a historical and cultural middle ground, were an in-between people, exiles at home. And whether identifying as white or black or mixed-race, they often took for themselves the name Creole, a wide-ranging word derived from the Portuguese and used to designate a New World-born descendant of Old World peoples. In their writings, these Creoles imagined themselves a united community, a Creole City, a place defined by its own uniqueness. From Twain to Faulkner, Truman to Tennessee, most every ensuing writer who would come to embrace New Orleans and its people owed a debt to these now largely untranslated, unread, and forgotten authors.

Several prominent members of the literary circle were buried in this very cemetery, including its founder and spiritual godfather, Charles Gayarré. Born in 1805, the descendent of early French and Spanish settlers, Gayarré fancied himself a backwater aristocrat: an educated man, voluminous writer, and sometimes politician, born into a city where the inflated mortality rate — due to disease and violence — was inversely proportional to the population’s literacy. In a writing career that spanned eight decades, he penned novels, plays, and essays for major national magazines, but it was his several volumes of history that cemented his reputation as New Orleans’s first and foremost man of letters. In his bestselling chronicles, he set out to encase the city’s past in what he called “a glittering frame”; to inject life into history; to compose a semi-factual narrative brimming with gilded embellishments, poetic romanticism, and, at times, outright bullshit. And though he whitewashed history, fabricating names and events and dialogue, Gayarré’s literary project worked. He wrote a history of this city that endures in the collective memory of its inhabitants.

Like any skillful biographer, I cultivated a knowledge of the man that could arguably rival what he knew about himself. I read his youthful writings and scoured archives for the rare unpublished jottings. I know that at the age of twenty he fathered a son with a family slave. I possess the knowledge, loathing the fact, that he named the boy after himself, before cutting him loose and disavowing parentage for the remainder of his years. I know that he lost every penny after foolishly investing in the losing side of the Civil War. I know that he enjoyed a cup of hot chocolate in his old age. I know that it rained at his funeral.

But after spending my entire graduate student life with the man, Gayarré remained just words on a page. Alive and vivid and sharply meaningful, but still just ink. As I silently scrubbed this anonymous tomb, I imagined tracking down his mausoleum to find it in a similar state of decay. His vault would be grand, imposing, much like the life of the man who’s remains it contained. But it would also be ravaged, forgotten, resembling so many other tombs scattered throughout St. Louis No. 1. By helping to restore his vault, I thought, I could get at the root of him. I could reach back into history and shake the hand of a dead man.

* * *

I scrubbed for three hours, until the XXXs had faded into the faintest of scratches. I asked Save Our Cemetery’s then executive director, Angie Green, if she might know the location of the De Boré family plot — the tomb of Gayarré’s mother’s lineage — where I thought the man must be buried. She did not know, but told me to follow her.

We weaved through the cemetery’s lanes, sidestepping tombs and tourists, searching for someone she described as St. Louis No. 1’s unofficial sexton. Within minutes we ran smack into him.

He was a sturdily-built man, dressed in white paint-splotched overalls and carrying a stepladder, bucket, and long-handled brush. His face was red from long hours in the sun. We had caught him hustling from one tomb to another.

“Do you maybe know where Charles Gayarré, the historian, is buried?” I asked, before even learning the stranger’s name.

“Know him?” he hollered in a sharp port of call accent that echoes in the voices of New Orleanians,“That’s my cousin!” before offering up a big, spirited hand to shake.

Still nameless, he guided me towards the back of the cemetery, near but not crossing into the “Protestant Section,” where Church law once dictated that the bodies of non-Catholics be laid to rest.

“Here he is,” he proudly pointed. “Charles Gayarré.”

The condition of the De Boré family tomb could not have been more magnificent. I ran my fingers across the plaster’s fresh coat of white paint, glittering in the sunlight. Over the carved and weather-worn letters of its marble plaques, all intact and uncracked. And along the intricate filigree of its antique wrought iron fence and cross that guarded the vault’s front, standing strong with the fine rust of age.

This was the handiwork of this same man, Ben Crowe, the Virgil to my Dante. He only recently resealed and re-whitewashed the tomb’s façade, he explained, as he had so many vaults across this cemetery. I followed him next to a nearby tomb belonging to Pierre Derbigny, a French-born patrician who became one of Louisiana’s first governors, that he had also meticulously restored. A decade ago, Crowe said, his dying mother informed him of their place as a distant branch on the Derbigny family tree. He didn’t believe her at first. They were a working-class family from a working-class slice of New Orleans. Nearing retirement age, he maintained bridges for the railroad, and gave little thought to history. But he scoured genealogical records, tore through tattered volumes of history, and traced his family’s local heritage back eleven generations, to some of the very founders of this city.

Crowe’s ancestral tree flourished to include many ancient Louisiana families — Derbignys and Denises, De Borés and Lebretons — and he soon began wandering the alleys of St. Louis No. 1, searching for their final homes. Those tombs he found in disrepair, he re-plastered, repainted, rehabilitated. In his spare time and on his own dime, he soon began transferring his research, the hours spent exploring these ancient lives, onto graveside markers, hand-built but gallery-quality, complete with portraits and timelines. I wanted to ask a dozen questions, but Crowe had a tough time explaining his recent obsession with the past.

I’d like to think that New Orleans is a city validated by its own clichés. The bacchanalian atmosphere, the corrupt politics and police force, the omnipresent threat of violence that runs a thin red line down every street, the beautiful rot and exquisite decay — these hackneyed tropes have existed for three hundred years, because each reveals a glimmer of truth.

One last cliché might just ring true. Perhaps only in New Orleans do the dead — and undead — walk freely among the living, just as we, alive and full of spirit, move alongside the departed. For Charles Gayarré, Ben Crowe, and myself, the past tugs at every fiber of our being. Searching for life in death, we are all just chasing ghosts. And sometimes we might find ourselves lucky enough to reach out and shake hands with the past.

I left Crowe with the promise to share my research and writing on his cousin Gayarré. He assured me that the next time he locates a relative’s crypt broken and busted we will plaster and paint it together. With bucket and brush in hand, he disappeared behind a row of crypts to check on another family vault.

Before heading out of the cemetery gates, I stopped by my own adopted tomb, which now looked at least slightly cared for, and promised to visit it again.

RIEN FERTEL'S writing has appeared in Garden & Gun and Oxford American. He is the author of three books, most recently Southern Rock Opera with the Drive-By Truckers.

Taylor Bruce